Do you remember that exact moment from your childhood - sploshing in through the back door, sopping wet and dripping all over the floor after enjoying a series of muddy puddles, with an enormous smile on your face? Do you recall that criticizing expression on an adult’s profile that dampened/squashed/ruined your delight with a mere glance?

It is absolutely true that children know how to have more fun, especially when it comes to experiencing the novelties of nature. Everything is a new, exciting experience for them, from jumping into a pile of leaves, to letting the water in the creek gently caress their tiny hands, and oh, the joys that can be had with clay!

Us adults? We are far too reserved to have spontaneous fun like that. We don’t want to waste time, or create more work by getting dirty. We tend to opt for the easy way out, staying clean and dry, every chance we get - after all, going to work, working from home, life in general and raising a family is definitely tiring. Yet, we are missing out on those very experiences that make us feel - and come - alive!

Unfortunately, the “easy way out”, the ultimate way to relax, has become that of the technological and digital kind. Traversing life on the internet is a clean activity, it is mostly indoors and it doesn’t strain our muscles, and it is certainly not dependent on rain. It’s safe enough to hide behind our screens, and let our children do the same, in part because everyone else is doing it; we have grown accustomed to it.

We check our email at various times of day, waiting for letters that have not yet arrived. We search for likes and comments on social media, simply because we want to be seen and heard. But, to be seen and heard, felt and understood, we need to communicate in other ways.

In order to rediscover life beyond the screen, we must admit that smartphones don’t need us quite as much as we need them. We need to know that people will wait for our reply, and that busyness and checking in is exhausting.

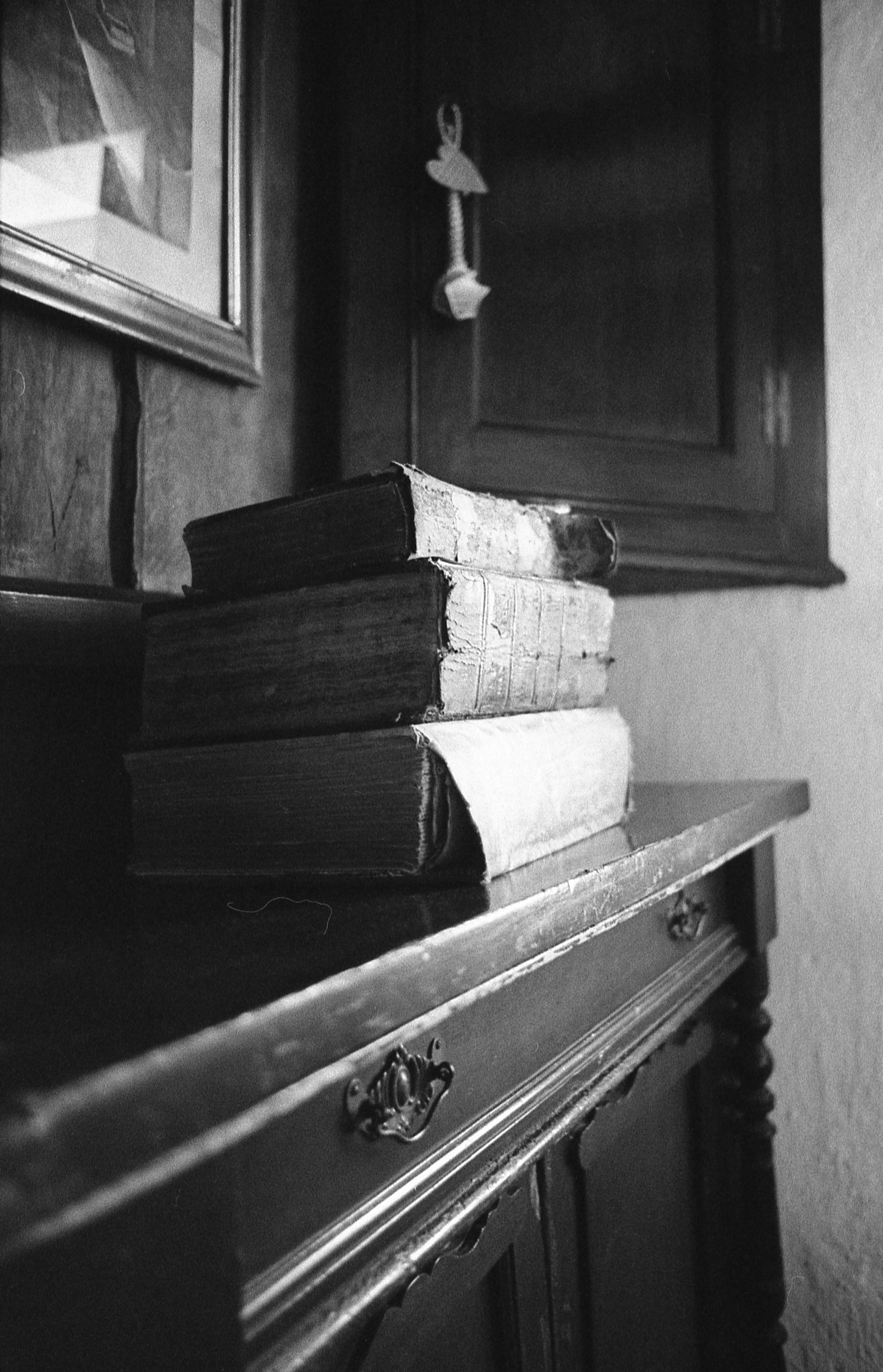

To get back to a simpler way of life - way before all this phone, laptop and connectedness craze started - takes courage!

It takes removing ourselves from electrical impulses, and replacing them with grounding instincts, which can be as uncomplicated as walking barefoot on the beach, or on your own grassy lawn.

The modern term for this healing time without distracting screens is digital detox. The concept is so novel that it has yet to be translated into every language. It is as easy as turning off your Wi-Fi for an entire day, or logging out of Facebook for a week, so that you are not tempted in any way to check in on what you are missing. Here’s a kind hint: it is much of a nothingness.

It may feel strange at first to disconnect, to be unavailable online. Just know that it gets easier every time you make the effort to do it.

And that life beyond the screen?

It is filled with hours and hours of meaningful things to do, it is teeming with face-to-face meetings over tea and coffee, it contains gardens, plants and animals of both the furry and feathered kind. And it is yours for the taking!

What can you do without a screen to entertain yourself, assuming that the word boredom does not exist?

Go for a walk in nature, far or near, on the sand or under trees.

Take photographs with a camera (not your phone) or sketch what you see in your journal.

Cook using your intuition and heart, skipping the recipes and meal plans.

Spend copious time with the people you know and love in person: playing, talking, dreaming, laughing.

Remember how much merrymaking and enjoyment you had as a child before computers and cell phones entered the sacred space of the family home. Those mechanical objects used to belong to businesses, yet somewhere along the way we have claimed them for our own, in the hopes that they would make our lives efficient, easier. And they have done that to a certain extent, but we have also brought into our private homes a good deal of the work stress and expectations of 24-hour availability…

If the mere idea of too much technology frustrates you, it is the ideal time to provide distance between you and your devices.

Start small, shutting your phone completely off at night. Log out of all accounts, making an extra step for yourself to check back in. Digital detox for one day a week, then for two. Gradually work your way up to an entire week of free time, carved out just for you.

What is stopping you from rediscovering life beyond the screen?

If you are so inclined, you can even Digital Detox With Us, in Breb, Romania. We can provide the backdrop of a beautiful landscape in which to (re)experience nature, gather up some foraging and homesteading skills and join in the daily activities (chopping wood, organic gardening, making fire and carrying water) of like-minded people, engaging in meaningful and essential conversations about the environment.